Why there are equations on a marketing website

Not because we’re trying to look clever.

Because marketing is a decision system under uncertainty.

Every day, teams make calls with incomplete information: what to test next, where to spend more, what to stop, and when to wait. Platforms optimise locally for clicks, impressions, or conversions. Businesses, on the other hand, live globally with budgets, trade-offs, risk, and opportunity cost.

That gap matters.

The equations you see across this site aren’t decoration. They’re reminders. Each one captures a hard-won idea about how decisions behave when data is noisy, incentives are misaligned, and certainty is impossible.

Equations are compressed wisdom. They force clarity. They don’t care about opinion, seniority, or confidence. They only care whether your assumptions hold up.

This article is a short tour of the ideas behind those equations, and why they shape how we approach marketing at D3.

Bayes’ rule: learning without panic

If there’s one idea that runs through everything we do, it’s Bayes.

Bayes’ rule is often written as:

New belief ∝ Old belief × New evidence

In practice, it says something simple but uncomfortable: you never start from zero. Every decision already carries an assumption. The question is whether you update that assumption calmly as evidence arrives, or overreact to the latest data point.

In marketing, Bayes shows up everywhere:

- A campaign spikes one week. Is that real, or noise?

- A channel underperforms for a few days. Is it broken, or just volatile?

- A test “wins”. How confident are you, really?

Bayesian thinking doesn’t eliminate uncertainty. It disciplines how you respond to it. You update gradually, in proportion to the strength of the evidence, rather than swinging from optimism to panic.

This is why we’re cautious about dashboards that scream certainty too early. A very convincing chart can still be wrong. Bayes reminds us that learning is incremental, not dramatic.

Measure properly. Think clearly. Decide calmly.

The influencer equation: structure beats individuals

One of the most misunderstood equations (you can stop sniggering now!)

This equation describes influence spreading through a network. The symbol p∞ doesn’t mean literal infinity. It means the steady state: the long-run pattern you settle into after influence has finished moving.

The matrix A represents the structure of the network: who is connected to whom, how strongly, and in what direction.

The meaning is simple and slightly brutal:

Once the system settles, influence is determined by structure, not by any single person.

If your message doesn’t fit the network, it won’t travel.

Confidence intervals: humility as a competitive advantage

Confidence intervals exist to answer one essential question:

How sure are we?

Most marketing mistakes don’t come from bad ideas. They come from overconfidence. A result looks strong, so teams scale too early. A drop looks scary, so they pull the plug too fast.

Respecting uncertainty isn’t caution for its own sake. It’s commercial discipline.

A quick word on the other equations

- Reward equations remind us that short-term wins can sabotage long-term performance.

- Market equations capture feedback loops, saturation, and diminishing returns.

- Betting equations formalise risk, payoff, and why “all-in” is rarely rational.

They sit quietly in the background, shaping how we think about trade-offs and timing.

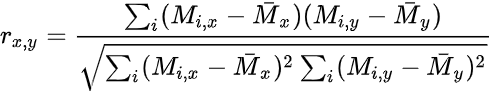

The advertising equation: correlation is not kindness

Correlation tells you whether two things move together. It doesn’t tell you why.

In advertising, this matters because correlation is easy to misread. If your measurement is wrong, every downstream decision is wrong.

The arithmetic always wins in the end.

What this means in practice

Marketing is not about certainty. It’s about making the best possible decisions, repeatedly, under uncertainty.

At D3, that means:

- Fixing measurement before scaling spend

- Designing tests that can actually teach you something

- Respecting uncertainty instead of hiding it

- Letting structure, evidence, and arithmetic do the heavy lifting

This isn’t about being clever.

It’s about being right more often than chance would allow.

That’s the promise.

Many of the ideas and equations referenced here are inspired by David Sumpter’s book The Ten Equations That Rule the World.